A tale of two tribunals is unfolding over Amgen’s European patent for antibody PCSK9 inhibitors. Two IP patent attorney Sheena Linehan unpicks the potentially profound consequences for life science innovators navigating the evolving European patent landscape.

When the Unified Patent Court (UPC) opened on 1 June 2023, it was quickly tested with a high-profile case: Sanofi launched a revocation action against Amgen’s European patent EP 3 666 797 B1, which covers antibody PCSK9 inhibitor therapies, including the blockbuster Repatha®. In a decision issued on 16 July 2024 (UPC CFI 1/2023), the UPC revoked the patent for lack of inventive step. The court held that development of antibody therapies targeting PCSK9 was an obvious next step based on prior art.

Yet, in stark contrast, the European Patent Office (EPO) has upheld the same patent in first instance opposition proceedings in light of the same prior art document. The EPO’s Opposition Division found that, while the prior art pointed to PCSK9 as a promising target for development of antibodies, there was a lack of a “reasonable expectation of success” regarding the therapeutic efficacy of antibody PSCK9 inhibitors—a critical factor in establishing inventive step under EPO standards.

This divergence is more than legal nuance. It goes to the heart of biotech innovation, where therapeutic development is uncertain, high-cost, and fraught with clinical risk.

A Divergence in Legal Reasoning

At issue is how to assess inventive step of a new biologic therapy when the prior art already validates the biological target. The UPC adopted a pragmatic view: if a skilled team is motivated to take the next logical step in developing the prior art, and does not foresee any particular difficulties in doing so, the claim lacks inventive step. The court did not require evidence that the skilled team would have a “reasonable expectation of success” in achieving a therapeutic effect in light of the prior art.

By contrast, the EPO emphasized the unpredictability of therapeutic outcomes in complex biological systems. It underscored that lack of direct evidence in the prior art for therapeutic efficacy meant that a skilled team could not have reasonably expected success—making the invention non-obvious under EPO jurisprudence.

The EPO also referenced EPO Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G2/21, which requires “plausibility” of therapeutic effect in patent applications for medical use claims. It concluded that if the prior art wouldn’t meet that standard, it can’t support a reasonable expectation of success either.

Why This Matters for Biotech and Biopharma Innovators

For life science companies, this difference isn’t academic. Development of therapeutics, including antibodies, is notoriously risky, with a roughly 90% failure rate from clinical candidate to approved drug. Around 40–50% of failures stem from lack of clinical efficacy, which reflects a failure in target validation.

If courts downplay this uncertainty and adopt an “obvious next step” standard, they risk undermining broad patent protection for first-in-class therapies—those built on unproven biology and bold clinical hypotheses.

The UPC’s stance could make room in the marketplace for second-in-class therapies — providing greater choice for patients — but it carries the risk of disincentivising innovation.

Strategic Choices in the European Patent System

The UPC and EPO are independent bodies. The EPO grants European patents, and patent owners can choose to validate their European patents nationally or as Unitary Patents which have unitary effect in participating EU member states. The EPO also provides a central post-grant opposition mechanism. Patent owners can opt out EPO-granted patents which have been validated as national patents from the UPC’s jurisdiction, at least during a seven year transitional period. The UPC rules on infringement and validity of Unitary Patents, and nationally validated patents which have not been opted out.

Amgen’s case puts the spotlight on a critical strategic decision: Should biotech innovators rely on the UPC, or stick with traditional national validation routes and courts? The answer may increasingly depend on how courts assess “inventive step” in complex therapeutic areas.

Notably, Amgen is also asserting its patent in a separate UPC infringement action against Sanofi and Regeneron, in respect of Praluent®, a structurally distinct but functionally similar antibody which they developed independently. The stakes are high—not just for the parties, but for the system’s coherence.

Global Trends and the Innovation Climate

Amgen’s broad antibody PCSK9 inhibitor claims have faced hurdles elsewhere. Corresponding patents in the U.S. and Japan were also invalidated, albeit for different reasons. The global trend suggests increasing scrutiny of broad antibody claims that are defined functionally rather than structurally.

This raises a broader policy question: Are innovators being fairly rewarded for high-risk, early-stage biologics development—or only for de-risked, follow-on products?

Key Takeaways for Life Sciences Companies

- EPO upheld Amgen’s patent, recognising the uncertainty and lack of a “reasonable expectation of success” from the prior art.

- UPC revoked the same patent, seeing the claimed invention as the next logical and routine step.

- Diverging approaches to inventive step create legal uncertainty and strategic complexity for innovators.

- Appeals pending in both venues will be closely watched—and could reshape European patent strategy for biologics.

Looking Ahead: Strategic Considerations for Biotech IP Teams

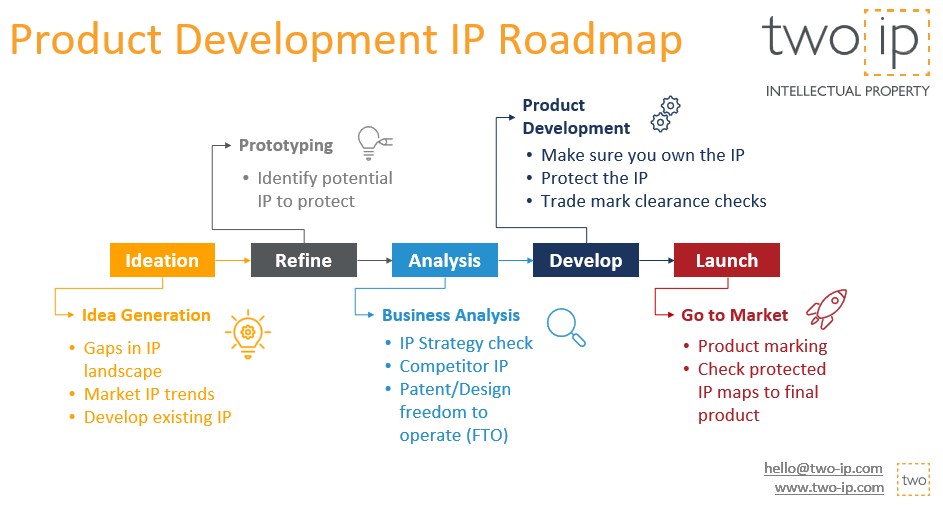

Until these appeals are resolved, life science companies should:

- Closely evaluate patenting strategies for functionally defined biologics and therapeutic uses.

- Consider opting out of the UPC for foundational or early-stage assets where clinical uncertainty is high, and a broad claim scope is desired.

- Strengthen EPO applications with data supporting plausible therapeutic effects, in order to support second medical use claim format.

Our patent and trade mark attorneys can help you work out what you should be doing to protect your IP and then help you do it. To get in touch, click here or email us at hello@two-ip.com.

Found this information useful? Click here to sign up for our monthly Two Insights newsletter.